For years, I have been telling people there is no relationship between volume and price. Occasionally, I meet an enlightened soul who agrees with me. More often, I am met with blank stares of disbelief.

Yes, I agree that, when you buy a few engineering samples, look at pricing on a distributor’s Website, and ask for quotes, the data is presented as if such a relationship existed. But once you begin negotiations, that relationship dissipates. The price you pay is a complex function of many variables. Coming up with a precise model for it exceeds the level of my mathematical skill. Pricing seems to be an art form, and it is influenced by factors like how badly a supplier wants your business. It depends on your reputation, how you pay your bills, your total spending on materials, the chosen channel, your negotiation attitude, geography, and more.

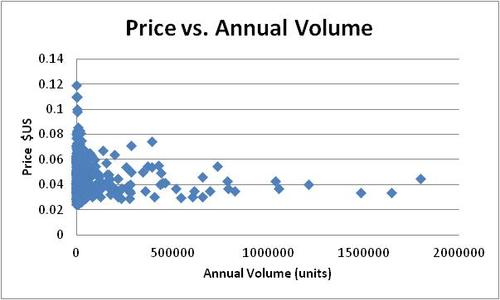

I can substantiate my proclamation regarding the volume/price relationship by using data from freebenchmarking.com. The Website has become the world’s largest independent database on electronic component pricing, and I can use it to explore pricing relationships. The figure below is typical of what I find when I make scatter plots of price vs. volume. My choice of which component to feature was somewhat arbitrary. It isn’t the largest component group or unique in any way. It is just very typical.

This plot, for a group of functionally equivalent capacitors, is made up of 642 price/volume data point pairs with volumes ranging from 1 unit to more than 1.5 million units per year. Pricing is gathered from our clients who represent a full spectrum of OEMs and EMS providers — from Tier 3 up to the largest Tier 1 users of components.

I see no price/volume relationship in this plot or any of the many other component plots I review. Some companies are getting better pricing for a handful of components than others buying hundreds of thousands of parts. I will concede that the price range appears to narrow with volume, but that might be because there aren’t that many companies buying such high volumes.

What does this mean for professionals in charge of sourcing and pricing? Here are some of my conclusions.

- Your head needs to be in the right space for negotiations, so get rid of old constraining paradigms. Understand your competitive position and your leverage points before you begin negotiations. Know which of your components are properly priced and which ones aren’t. Your pricing is set by your negotiations, not by some old cost-plus-volume curve.

- You must know why the supplier wants to do business with you and how you can increase your leverage and supply options. Know what factors you can push on to increase the supplier’s desire.

- Don’t let decreasing volume become an excuse for accepting price increases or forgoing cost reduction. In fact, challenge all attempts at price increases until you are absolutely convinced there is no alternative. Remember that there is no dominant relationship between price and volume.

On a related note, don’t get yourself into contracts where your price is conditional on something you can’t verify. Some companies sign up for “most favored nation” clauses that promise best pricing but offer no means of verifying it is being received. Sometimes, these contracts work. Often, they don’t.

By Ken Bradley – Lytica Inc. Founder/Chairman/CTO